California recognizes emotional distress damages caused by witnessing physical harm to close family members

Lay persons are often surprised to learn one may recover for their own emotional distress due to the physical injury of another. However, under California law, a party who experiences no physical harm may still claim emotional distress for the injury to a close family member as long as they contemporaneously perceive the injury caused by the defendant. Nonetheless, there are important limitations on recovery for what is called “bystander” emotional distress. Most importantly, the person claiming distress must have perceived the harm from the defendant as it is happening and been aware of such harm. (Dillon v. Legg (1968) 68 Cal. 2d 728, and Thing v. La Chusa (1989) 48 Cal. 3d 644.) Dillon recognized bystander recovery for negligent infliction of emotional distress, sometimes given the odd acronym “NIED.” [1] After the landmark Supreme Court holding in Dillon, the appellate court in Thing gave such amorphous claims crucial limitations so that a defendant who causes physical harm to a plaintiff is not also liable to each and every person who witnesses this harm. In the absence of physical injury or impact to the plaintiff, damages for emotional distress should be recoverable only if the plaintiff: (1) is closely related to the injury victim; (2) is present at the scene of the injury-producing event at the time it occurs and is then aware that it is causing injury to the victim; and (3) as a result suffers emotional distress.

In light of the tendency of California courts to expand the scope of potential claims, there is tension between the limitations found in Thing and factual patterns presenting sympathetic claims for negligent infliction of emotional distress. These include situations that do not present a classic scenario such as a parent physically present at the very scene where their child is harmed. Subsequent case law has sought to define how modern technology impacts the requirement that someone be “present at the scene” and is “aware” of the conduct which is causing a family member’s physical harm.

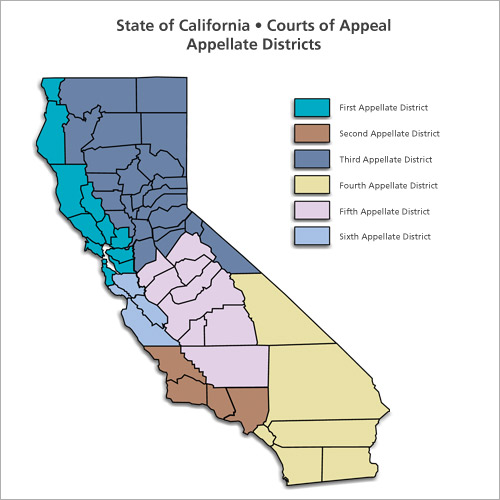

It is therefore important that in Downey the Fourth District, Division One, held a party may state a claim for NIED even where they perceive the injury to a loved one by way of a telephone call. (Downey v. City of Riverside (April 26, 2023) D080377.) However, such a plaintiff must also plead and prove the person suffering emotional distress was aware of the connection of the defendant to the harm suffered by their loved one. Plaintiff in Downey was the mother of a young woman injured while driving and, in fact, the two were talking on the telephone during the car crash. The mother stayed on the call though her daughter stopped speaking; a Good Samaritan then came to aid the daughter and asked the mother to hang up and call 911 for help. The mother and daughter sued the other driver, the homeowner adjacent to the intersection near the collision, and the City of Riverside, which maintained this intersection. The allegation against the latter two was that the accident was caused in part by the design of the intersection and/or homeowner’s maintenance of vegetation blocking the view of motorists.

Riverside and the homeowner filed demurrers as to the mother’s claim, arguing neither could claim negligent infliction of emotional distress. The demurrer was sustained without leave to amend by the trial court but the appellate court reversed. A two-to-one majority held the mother had failed to properly plead she was aware of some sort of connection between, on the one hand, her daughter's harm, and, on the other hand, the negligence of Riverside and the homeowner. The court further held the mother should be allowed to amend her complaint to plead such knowledge.

Negligent emotional distress is an element of negligence and is not plead as a separate tort as is “intentional infliction of emotional distress”

Of course, negligent infliction of emotional distress is not a separate cause of action but rather an element of damages recognized as compensation for negligent conduct. (Burgess v. Superior Court (1992) 2 Cal. 4th 1064, at 1072.) A plaintiff claiming physical harm due to another’s negligence may therefore also claim damages for the emotional distress caused by the physical harm. Moreover, close family members who witness this harm may claim such distress, subject to certain strict limitations. [2]

By contrast, intentional infliction of emotional distress is predicated upon a defendant’s unprivileged commission of an “outrageous act" with the intent to inflict mental suffering, thus requiring 1) extreme and outrageous conduct by the defendant with the intent of causing emotional distress; 2) severe or extreme emotional distress suffered by the plaintiff; and 3) actual and proximate causation of the emotional distress by the alleged outrageous conduct. (Christensen v. Superior Court (1991) 54 Cal. 3d 868, at 903.) In order to recover on this theory, a plaintiff must plead and prove that defendant’s acts were so extreme and outrageous as to exceed all bounds of decency and behavior beyond that normally tolerated in a civilized society. (Cervantez v. J. C. Penney Co. (1979) 24 Cal. 3d 579, at 593; Yurick v. Superior Court (1989) 209 Cal. 3d 1116, at 1128.) As the court stated in Christiansen, “[t]he defendant must have engaged in conduct intended to inflict injury or engaged in with the realization that injury will result.” The chief exception to the requirement of “intent” is where a defendant acts in “reckless disregard” of the plaintiff and with “substantial certainty” their conduct will cause severe emotional distress. (Id., p. 903.)

Plaintiff could recover even though she “observed” the incident from another location by listening to a phone call

The Downey court cited with approval to Ko v. Maxim (2020) 58 Cal. App. 5th 1144, where the Second District, Division Seven, ruled a “bystander” to physical injury to a close family member includes someone who observes the harm through electronic means. This is important because Thing provided a bright line test regarding the elements of a bystander’s claim for negligent infliction of emotional distress by stating a close family member may recover where they are 1) present at the scene when the injury-producing event happens, and 2) are aware the event is causing injury.

Plaintiffs in Ko brought claims for negligent infliction of emotional distress alleging an in-home nurse employed by defendant Maxim abused their disabled son while they were not at home. The Kos alleged they witnessed the abuse of their son in real-time via a livestream video and audio on a smartphone from a “nanny cam.” The trial court ruled the parents could not state a claim for negligent infliction of emotional distress because they were not physically present at the time of the harm to their son. The appellate court reversed and held that a “live stream” of an event constituted sufficient “presence” to meet the requirements of Thing and Dillon. Specifically, Ko discussed the technological advances which have occurred since 1989 and explained these changes make it possible for someone to be present virtually in a manner not previously possible and therefore to observe harm to a family member. Thing held the right to recovery is based upon the “impact” of the actual observation of harm, and thus “distinguishes the plaintiff’s resultant emotional distress from the emotion felt when one learns of the injury or death of a loved one from another, or observes pain and suffering but not the traumatic cause of the injury.” (Thing, 48 Cal. 3d at 666.)

Downey therefore held the plaintiff mother had “contemporaneous observance” of both the incident and the harm her daughter suffered even though she was in a different location and merely heard but did not see, the crash. The plaintiff had met the “contemporaneous observance” element of the claim for emotional distress by virtue of the facts plead:

. . . Downey [mother] heard Vance [daughter] take an audibly sharp, gasping breath; her frightened or shocked exclamation: “Oh!”; and the simultaneous, or near-simultaneous sounds of an explosive metal-on-metal vehicular crash; shattering glass; and rubber tires skidding or dragging across asphalt. Downey had not heard the sounds of skidding tires or squealing brakes in the seconds immediately preceding the impact. Then and there, Downey knew from the combination of the sounds she heard, and from having directed Vance where to drive, that Vance had been injured in a high-velocity motor vehicle collision at or near Via Zapata at Canyon Crest Drive.

As the sound of tires skidding or dragging across asphalt diminished, and having heard no sounds or vocalizations from Vance, Downey understood Vance was injured so seriously she could not speak. Downey immediately left her office, telling people there something like, “I have to go, my daughter has been in a car accident, I have to go.” As Downey ran to her car and started driving toward the scene of the incident, she called out to Vance. For a time, Downey heard nothing, but then heard the sound of rustling in Vance’s car. Downey started screaming into her phone, “Can you hear me? Can you hear me? I can hear you, can you hear me?” She then heard a male voice say something like, “Would you stop? I’m trying to find a pulse.” Downey waited, then asked, “Is she alive?” Moments later, the man said, “She breathed. I got a breath.” He then said something like: “What I am going to tell you to do is going to be the hardest thing you will ever do in your life. I want you to hang up your phone and call 911, and have them respond to Via Zapata and Canyon Crest Drive in Riverside.” (Downey, pp. 4-5.)

However, plaintiff did not plead she was aware Riverside and the homeowner had any connection to the harm she observed

The City and homeowner argued the complaint did not plead a sufficient causal connection between their actions and the emotional distress supposedly suffered by the plaintiff, such as her familiarity with and awareness of the dangerous conditions they created at the intersection.

This is because a plaintiff suing a particular defendant must plead not only observance of the actual harm but, as to a specific defendant, the “‘contemporaneous sensory awareness of the causal connection between the negligent conduct and the resulting injury.’” (Bird v. Saenz (2002) 28 Cal. 4th 910, at 918, quoting Golstein v. Superior Court (1990) 223 Cal.App. 3d 1415, at 1427-1428.) In Bird the Supreme Court reversed the Second District, Division Seven, which had in turn reversed the trial court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the medical malpractice defendants. Writing for a unanimous court, Justice Werdeger explained the defendants were entitled to summary judgment as the plaintiffs were not present at the time the medical malpractice occurred and were not aware until later that the defendants had caused the harm. This was true even though there had been a call for a thoracic surgeon over the loudspeaker at the hospital because such a general announcement would not tell anyone in the waiting room anything about a specific surgical procedure being performed.

Plaintiff in Downey was permitted to amend to plead facts showing, at the time of the accident, awareness of the relationship of the defendants to the collision

In an opinion written by Justice O’Rourke, to which Justice O’Connell joined, the majority in Downey held Riverside and the homeowner were required to plead awareness of a connection between the defendants who supposedly created a dangerous intersection and the plaintiff who observed the harm. Consequently, the trial court’s judgment of dismissal was vacated and the matter remanded to the trial court with instructions to permit the plaintiff to plead her awareness of the negligence of both Riverside and the homeowner. Plaintiff, of course, maintained she had such awareness because she had been giving her daughter directions just before the crash and therefore knew where her daughter was, and was familiar with the intersection at issue and its problems.

Justice Dato concurred the judgment in favor of the demurring defendants should be set aside but argued the demurrer should have been overruled by the trial court. The dissent argued a plaintiff who observed harm to a close family member should not have to plead awareness, at the very time of injury, of the relationship of each defendant to the harm. According to the dissent, language in Bird indicating a plaintiff must meet this hurdle should be limited to a medical-malpractice context because in such suits “there is seldom a readily-perceptible traumatic incident.” Here, by contrast, the plaintiff knew an accident was happening and that her daughter was injured.

Advice for practitioners pleading and defending claims of negligent infliction of emotional distress where observed electronically

Plaintiffs seeking to claim emotional distress by way of an ordinary phone call, Zoom meeting, FaceTime call, or other methods of “livestreaming” should be aware of the holdings in both Ko and Downey. It should not matter that the stream involves, audio, video, or a combination of the two as long as the facts show “contemporaneous observance” of harm to a close family member.

However, plaintiffs are advised to also plead some minimal knowledge of the relationship of each particular defendant to the harm. Specifically, each plaintiff should plead knowledge that the family member observing the harm is aware of the relationship of each defendant to the harm and, in particular, how their breach of the duty of due care contributed to the harm.

By contrast, defendants should be aware of the pleading requirements outlined in Thing, Ko, and Downey and should be ready to test pleadings by way of demurrer. They should also propound specific discovery as to what knowledge the plaintiff had as to each defendant's relationship to the harm at the time it occurred. Such discovery may be a necessary prerequisite to a motion for summary judgment and/or summary adjudication seeking to bar damages for negligent infliction of emotional distress.

Justice Dato concurred the judgment in favor to the demurring defendants should be set-aside but argued the demurer should have been overruled by the trial court. The dissent argued a plaintiff who observed harm to a close family member should not have to plead awareness, at the very time of injury, of the relationship of each defendant to the harm. According to the dissent, language in Bird indicating a plaintiff must meet this hurdle should be limited to a medical-malpractice context because in such suits “there is seldom a readily-perceptible traumatic incident.” Here, by contrast, the plaintiff clearly knew an accident was happening and that her daughter was injured.

Advice for practitioners pleading and defending claims of negligent infliction of emotional distress where observed electronically

Plaintiffs seeking to claim emotional distress by way of an ordinary phone call, a Zoom meeting, or a FaceTime call, or other method of “livestream” should be aware of the holdings in both Ko and Downey. It should not matter that the stream involves, audio, video, or a combination of the two as long as the facts show “contemporaneous observance” of harm to a close family member.

However, plaintiffs are advised to also plead some minimal knowledge of the relationship of each particular defendant to the harm. Specifically, it is advisable that each plaintiff plead the knowledge that the family member observing the harm is aware of the relationship of each defendant to the harm and, in particular, how their breach of the duty of due care contributed to the harm.

By contrast, defendants should be aware of the pleading requirements set forth in Thing, Ko, and Downey and should be ready to test pleadings by way of demurrer. They should also propound specific discovery as to what knowledge the plaintiff had as to each defendant's relationship to the harm at the time it occurred. Such discovery may be a necessary prerequisite to a motion for summary judgment and/or summary adjudication as to claims for negligence infliction of emotional distress.

1- Not to be confused with Pharrell William’s band “N.E.R.D.”2: A separate discussion is required to define who qualifies as a “close” relative, but persons who may inherit property under intestate law succession usually qualify.

2 - A separate discussion is required to define who qualifies as a “close” relative, but persons who may inherit property under intestate law succession usually qualify.