A landowner owes a broad duty of due care to almost anyone else, no matter the circumstances, unless California public policy clearly dictates a reason to depart from this broad rule

In California, Civil Code section 1714(a) defines the duty of due care owed in a broad fashion, failing to limit the persons to whom the duty is owed. Rather, this section states vaguely that “everyone” owes a duty of due care “to another:”

Everyone is responsible, not only for the result of his or her willful acts, but also for an injury occasioned to another by his or her want of ordinary care or skill in the management of his or her property or person, except so far as the latter has, willfully or by want of ordinary care, brought the injury upon himself or herself.

However, in the landmark case of Rowland v. Christian (1968) 69 Cal. 2d 108, the Supreme Court held that not all persons owe a duty of due care to all other persons in all circumstances. As the Supreme Court explained 43 years later, Rowland provides there are several considerations which, when balanced by the court, may justify an exception to the general duty of reasonable care embodied in section 1714. (Cabral v. Ralphs Grocery Co. (2011) 51 Cal. 4th 764.) As Cabral set forth, these considerations, sometimes called the “Rowland factors” include:

. . . [T]he foreseeability of harm to the plaintiff, the degree of certainty that the plaintiff suffered injury, the closeness of the connection between the defendant's conduct and the injury suffered, the moral blame attached to the defendant's conduct, the policy of preventing future harm, the extent of the burden to the defendant and consequences to the community of imposing a duty to exercise care with resulting liability for breach, and the availability, cost, and prevalence of insurance for the risk involved. (Id., p. 771.)

According to Cabral, courts only balance the landmark “Rowland factors” and consider whether or not a duty of due care is owed where there are clear “public policy reasons” for doing. This is because “in the absence of a statutory provision establishing an exception to the general rule of Civil Code section 1714, courts should create one only where ‘clearly supported by public policy.’ [Citations.]” (Cabral, 51 Cal. 4th at 771, quoting Rowland, 69 Cal. 2d at 112.) Indeed, Cabral teaches that under any Rowland analysis of duty:

. . . [T]he Rowland factors are evaluated at a relatively broad level of factual generality. Thus, as to foreseeability, we have explained that the court's task in determining duty ‘is not to decide whether a particular plaintiff's injury was reasonably foreseeable in light of a particular defendant's conduct, but rather to evaluate more generally whether the category of negligent conduct at issue is sufficiently likely to result in the kind of harm experienced that liability may appropriately be imposed. . . . (Cabral, 51 Cal. 4th at 772.)

This broad formulation of duty has led California courts to effectively foreclose the ability of landowners who, by any measure of common sense, should not be held liable to have their case dismissed before trial. This is so despite the obvious misbehavior of the plaintiff in causing the harm. In other words, landowners must now defend actions where the actions of the plaintiff are indefensible because they cannot obtain summary judgment by making a “no duty” argument.

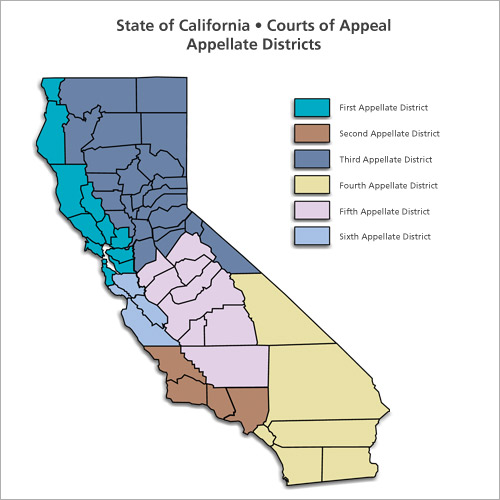

As but one example, in Razoumovitch v. Hudson Ave. LLC (May 12, 2023) B316606, the Second District, Division Seven [1], issued an opinion holding a tenant who accesses a roof area after being locked out of their apartment is owed a “duty of care” by their landlord. This is true even where the roof area is not designed to be accessed by tenants. [2]

Raasomovitch was injured while trying to break into his own residence and appeals after his landlord is granted summary judgment

There is no doubt Rasomvitch was on the roof not due to any invitation, whether express or implied, but, instead, because he needed to circumvent the locked door and find a more unusual method of entering the premises:

Razoumovitch explained [at deposition] he and two roommates lived on the top floor of their four-story apartment building, in a unit with a balcony. On the night of his fall, Razoumovitch and one of his roommates, Gonzalo Pugnaire, returned to the apartment at 1:30 a.m. after having drinks at a bar and discovered they had locked their keys in the apartment.

Their third roommate was either not home or not responding to their attempts to get his attention. After repeatedly trying without success to reach the off-site building manager, Razoumovitch and Pugnaire went to the roof of the building where, attempting to enter their apartment through the balcony, Razoumovitch lowered himself over the edge of the roof, so that he hung from the edge with his feet dangling in the air. After inching his way along (what counsel for the 726 Hudson defendants called) a “roof outcropping” where he hung at an uncertain distance above his balcony, Razoumovitch attempted to drop onto the balcony’s thick masonry wall. On landing there, however, he lost his balance and fell. Asked if there was any emergency circumstance requiring him to get into his apartment, Razoumovitch answered, “Well, it was just needing to be home and, you know, have a place to sleep.” The 726 Hudson defendants asserted Razoumovitch admitted “there was no emergency or pressing need for him to immediately access his apartment that night . . . . (Id., pp. 3-4.)

Razoumovitch argued the landlord should have restricted his access to the roof, which access was made necessary, of course, because Razoumovitch had been locked out of his apartment. Said plaintiff would not utilize the services of a locksmith or wait until the daytime when the landlord could be contacted; in fact, he insisted on attempting to enter the apartment by way of dangling from the roof and then argued the landlord should have “warned” him this was dangerous:

[Razoumovitch] alleged the defendants “were responsible for creating the dangerous condition that caused [his] injuries” and failed to warn him of any dangerous condition. Specifically, he alleged they had not sufficiently restricted access to the building’s roof, had not placed sufficient barriers around the roof’s perimeter, and had not placed an alarm or other device on the roof-access door that would have warned them that someone was accessing the roof. (Id., p. 2.)

The Hon. Audra Mori of the Los Angeles County Superior Court granted a motion for summary judgment brought by the defendant landowners. Plaintiff appealed, and Justices Segal and his colleagues in the Second District reversed.

Public policy does not indicate there should be an exception to the rule a landowner owes a duty even though the tenant was on the roof without the encouragement of his landlord

Razoumovitch noted the defense had attempted to apply the analysis of duty to the specific facts of the case, an approach no doubt followed by many other jurisdictions and one which might appear to be the approach most logical. The Second District, however, characterized this as a “mistake” and found these specific facts not dispositive. Rather, according to its reading of Cabral and Rowland, a court should instead “consider whether carving out an entire category of cases from that general duty rule is justified by clear considerations of [public] policy. (Razoumovitch, p. 14, citing to T. L. v. City Ambulance (2022) 83 Cal. App. 5th 864, at 876.) Razoumovitch did not, however, sufficiently discuss how one would decide whether the facts here — a tenant who is locked out making a foolish attempt to enter an apartment via the roof — fall within one “category of cases.” In other words, how may one distinguish between a class of cases where a duty is owed versus another category, where a duty is not, without considering the “specific facts” of that case.

Razoumovitch thus concluded the general duty of due care applied here because the defense had not shown there were clear public policy considerations that indicated otherwise. While the Second District did discuss and distinguish other case law cited by the defense it did not discuss in any real detail California public policy vis a vis the bizarre behavior of the plaintiff. All of the following appear to indicate that a logical and fair consideration of public policy does not favor permitting recovery by a plaintiff such as Razoumovitch:

- Plaintiff caused this situation because he became locked out of his apartment

- The landlord gave no encouragement to use the roof area in question

- There is no indication the landlord has promised to provide 24-hour “lockout service” or, for that matter, that plaintiff paid for such as part of his rent

- There may have been other roommates in the apartment at the time plaintiff attempted to enter

- Plaintiff had been drinking at the time of the incident

- Despite this, plaintiff attempted, late at night, a move that required him to lower himself from the roof and then dangle his feet in the air

Razoumovitch did discuss the oft-cited proposition that someone is not owned a duty of due in regards to warning of an obvious defect. But the court also noted this rule has a crucial exception and does not apply where the injury is “foreseeable” because the plaintiff has a “necessity” to encounter the harm. (Kinsman v. Unocal Corp. (2005) 37 Cal. 4th 659, at 673.) Of course, it may be obvious why this exception for the necessity to encouter an obvious danger should not apply to Razoumovitch, as he admitted there was no medical, safety, or pending emergency requiring him to enter the apartment and, therefore, he could have spent the night anywhere else he chose. Still, the Razoumovitch court somehow found Kinsman, where the plaintiff was exposed to asbestos while working at an oil refinery facility, relevant as to whether a duty was owed to warn Razoumovitch of the obvious danger from the roof. The Second District therefore tersely stated the defendants “do not address this exception to the general rule that a landowner has no duty to remedy or warn of an obvious danger” and found the defendants owed plaintiff a duty of due care. (Razoumovitch, p. 17.)

The appellate court also held defendants had not shown they were entitled to summary judgment on the grounds they were not the proximate cause of the harm

Razoumovitch also discussed the defense argument that they were not the “proximate cause” of the harm because the injury was not “foreseeable.” Of course, proximate cause is ordinarily considered a legal issue, this prong of caution being distinguished from “cause in fact,” which requires consideration of disputed facts. Nevertheless, Razoumovitch found that here the issue of proximate cause could not be decided as a matter of law “on the record here,” noting at page 19 that it may have been ”necessary” for plaintiff to attempt to access his balcony by way of the roof:

. . . [E]vidence regarding the proximity of Razoumovitch’s balcony to the edge of the roof and the evidence tending to show at least some degree of practical necessity for entering his apartment through the balcony, causation was a factual issue. [3]

1 -The opinion by Justice Segal was joined by Justices Perluss and Feuer

2 - One could imagine a rooftop area developed for the use of tenants, but there here was no allegation there was a rooftop garden or deck designed for relaxation or recreation

3 - While the court did not expressly adopt a rule a landlord owes a duty to provide a “lockout” service at all times, the fact the court mentioned this argument multiple times shows some at least sympathy for the situation plaintiff caused for himself.